All significant jazz musicians are innovators, finding new expression in every solo, adding to the vocabulary and the lore of America's music, but some are a little farther out in the forefront. It was great to listen to Billy Taylor's intonation and richness of tone, his way of developing and enriching a ballad. It was wonderful and surprising to hear Bengt Hallberg and realize that even in the early 50s, Europe was producing expressive talents whose technique made even Miles Davis sit up and take notice. But John Lewis was taking jazz composition in a direction no one had thought of. And Thelonious Monk had taken it, and was continuing to take it, in directions no one else could possibly have thought of. Lewis took everything that he had thought about while playing on gigs and sessions with some of the giants of his era, including his contribution to the gamechanging Miles Davis nonet, and decided that he could go his own way and take it further. Monk never went any way except his own.

The earlier session is a Sonny Rollins gig, the current one is a Monk gig. The difference is more historical than aesthetic. They're both great to listen to, and if you were there at the time, that's pretty much all you'd be thinking about.

Time changes your perspective. When I was teaching college courses in the early 2000s, and I'd show The Wild One, my students would invariably fix on a scene that I would scarcely have noticed as a teenager. It's after the mob catches up with Brando. They take him to a garage, put him down in a chair, and the chief bully starts beating him. Brando snarls back, "My old man used to hit me harder than that." The lines my friends and I remembered, and recited back and forth to each other, were lines like, "What're you rebelling against, Johnny?" "Whaddya got?" Or "I don't like...cops." Or "Write my mother and tell her I'm in jail! Tell her to send me a case of beer!" When I would ask my students, "What do we know about Johnny?" They'd say "His father beat him." And yeah, it's there. It is one key to his personality. But the emphasis is different.

And so with these two recording sessions. Listening to Rollins and the MJQ, it's hard not think they won't be making too many more like this. They'd record with other soloists again, including Rollins. Just three years later, they'd record a live concert at Music Inn in Massachusetts with Jimmy Giuffre, and again two years after that with Sonny Rollins. Both of those feature great performances by two great reedmen, but they're both MJQ concerts.

And so with these two recording sessions. Listening to Rollins and the MJQ, it's hard not think they won't be making too many more like this. They'd record with other soloists again, including Rollins. Just three years later, they'd record a live concert at Music Inn in Massachusetts with Jimmy Giuffre, and again two years after that with Sonny Rollins. Both of those feature great performances by two great reedmen, but they're both MJQ concerts.All of which is a distraction from the session at hand, which is terrific. How can it not be? Monk and Rollins at top form. Actually, one member of the MJQ, Percy Heath, who always adds something special.

There are a bunch of Willie Joneses in jazz, two of whom are drummers, and none of whom are related, although the current one, a drummer who's played with Horace Silver, Herbie Hancock, Artuo Sandoval and others, calls himself Willie Jones III, to distinguish himself from Monk's drummer, who was sometimes called Willie Jones, Jr., to distinguish him from Willie Jones the piano player, sometimes known as "the piano wrecker" because he could play an upright piano so hard it would vibrate, who recorded with Gene Ammons and Clark Terry, among others. Willie Jr. is playing his first recording gig here with Monk. He would have a short career but agood one, including Charles Mingus's classic Pithecanthropus Erectus.

Julius Watkins was almost certainly the first significant French horn player in jazz, and there have been precious few since. Another of Detroit's seemingly endless stream of jazz greats, he heard a French horn when he was nine, fell in love with it, and the horn was life from there on. Jazz came later, as it became clear that there were not going to be openings for black hornists in major symphony orchestras. Also, he wanted to solo, and that meant jazz.

He does solo on this date with Monk, to particularly powerful effect

on the ten-and-a-half minute "Friday the Thirteenth," and when he and Rollins play together, the tonal quality is wonderful, and very appropriate for Monk's music.

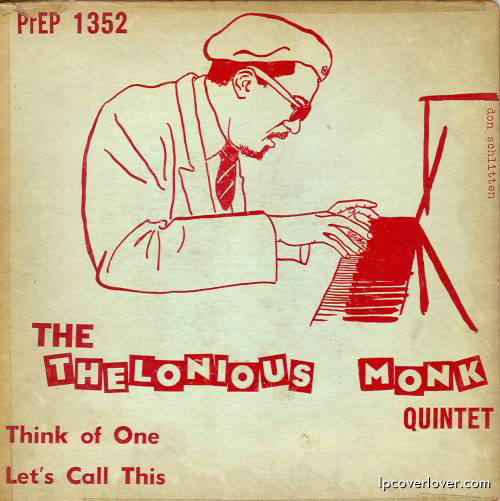

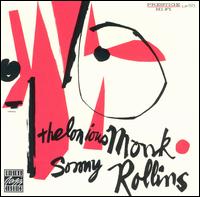

on the ten-and-a-half minute "Friday the Thirteenth," and when he and Rollins play together, the tonal quality is wonderful, and very appropriate for Monk's music.No 78s for these five and ten-minute cuts."Let's Call This" and "Think of One" were released on EP. The whole session was on a 10-inch called Thelonious Monk Blows for LP, and later on 12-inchers: Monk and Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins.

No comments:

Post a Comment